Behind the Pages

The research necessary to write a compelling work of historical fiction can seem daunting; the facts of worlds far away, both in time and distance, different languages, mores and cultures… I feel privileged to spend so much of my time learning about the places and times I want to write about and thought I’d share some of the facts behind the fiction. For me, a world divorced of history appears flat, it’s horizons narrow. This is my very modest attempt to make the world rounder, fuller and maybe, more interesting.

Rereading Vasily Grossman

Rereading Vasily Grossman, I was struck by how much I had forgotten, by how fresh and relevant his work remains. His courage, his belief in human freedom and human worth on its own terms, is uniquely valuable.

Rereading Vasily Grossman, I was struck by how much I had forgotten, by how fresh and relevant his work remains. I remember loving his prose when he was first available in the west, in the heady days of Perestroika and its aftermath, with the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union. Then, I’d been moved by Grossman, particularly his reflections in Forever Flowing about freedom and humanity that appeared to echo the new mood on the streets of Moscow and Prague and Berlin where I wandered and studied in those heady days. I learned from Grossman what had befallen the Jews (and his own mother) during the German occupation and knew he’d spent 1000 days at the front, at Stalingrad, the correspondent for the Red Star, until he was reassigned to follow Soviet troops all the way to Berlin.

I did not know that as he accompanied Soviet troops in their pursuit of the German Army, they discovered evidence of Nazi atrocities committed by SS Sonderkommando—93 Jewish families, murdered, their children with poison smeared on their lips. I did not know that in the summer of 1944, Soviet soldiers, Grossman with them, happened upon the death camps of Poland—Majdanek, Treblinka, Belzec and Sobibor. I never read The Hell of Treblinka, published in the Soviet Magazine, Banner, in 1944. And it wasn’t until I began researching my novel, You, With Your Waiting, that I discovered Grossman’s Black Book (co-edited in part by Ilya Ehrenberg, the Black Book is a compilation of eye-witness accounts of the Nazis’ wholesale attempt to exterminate Soviet Jewry). Set in type in 1946 and ready for release in 1947, the Black Book was derailed by the Soviet desire to avoid particularizing Jewish suffering during the war. It wasn’t released in Russia until 2014, the authorities having already effectively eradicated the history of the Holocaust by Bullets in Soviet territory and any knowledge of the extermination of Jews during WWII in its territory.

Nevertheless, my limited encounter with Grossman’s work has stayed with me all these years. He wrote the Soviet experience of WWII, the Purges and the Gulags, mass starvation deliberately inflicted on the Ukraine—in honest, clear-eyed prose briming with tenderness for humanity and at a time when these subjects were off limits to Soviet writers. Nominated for the Stalin Prize twice, Grossman’s name was crossed off the list by Stalin himself. Worse, Grossman’s anti-totalitarian novel, Life and Fate, was banned. He’d submitted it to Banner in 1960, thinking that after Stalin’s death in 1953, in the midst of Kruschev’s Thaw, the novel had a chance. The KGB arrested the manuscript, calling Life and Fate more anti-Soviet than Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago. In so doing, the authorities further erased the memory of the Shoah in the Soviet Union. Fortunately, two copies survived. Still, the novel did not appear in the west until 1980 and in Moscow in 1989.

I write about Grossman now because not only did his work prove invaluable to my own—his writing fostered my own passion for the history of WWII in the Soviet Union—but his work remains deeply relevant. First as a witness and compiler of testimonies of the mass murder of Jews. In a world increasing indifferent to the facts of the Shoah and the rise of Shoah denial in the west, Grossman is essential. His courage, his belief in human freedom and human worth on its own terms, is uniquely valuable. As I look around me at the increasingly violent political rhetoric, the loss of civility and empathy, the demonization of others and the call for death based on ethnicity, political affiliation or personal history, Grossman is more meaningful, more necessary than ever.

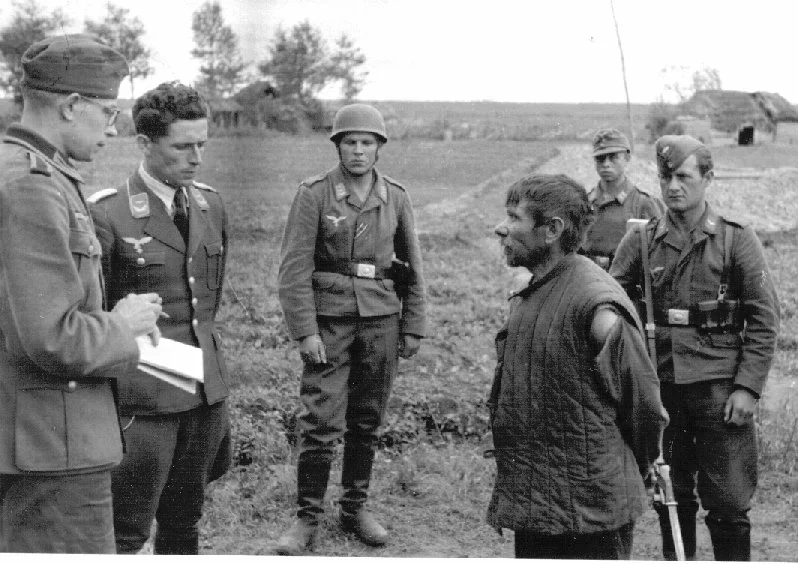

Source: Shayer, Maxim D. “Grossman’s Resistance.” Holocaust Resistance in Europe and America: New Aspects and Dilemmas. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017, pp 134-163.Photo Source: Yad Vashem (yadvashem.org)

Jews, Mountains and Germans

Much of my novel, You With your Waiting, takes place in the Caucasus, the area between the Black and Caspian Seas stretching 1200 kilometers east to west and 500 kilometers north to south. During the German occupation of the region during WWII, the Nazis murdered as many as 70,000 Jews in the spa towns and villages sprinkled throughout the mountainous territory. This number represents more than half of all Jews murdered in the Russian SSR in 1942-43. And yet there were stunning stories of rescue and survival. One story, fictionalized in You, With Your Waiting, recounts the daring attempt to rescue 32 children by the Circassian community in Beslenei. I do not name Beslenei in the novel but I do name the mayor of the town, the man who insisted on an ingenious plan to save Jewish orphans through adoption— Murzabek Okhtov.

In April of 1942, a convoy of orphaned children escaped besieged Leningrad, travelling across frozen Lake Lagoda, then slowly making its way south toward the Caucuses. After their train was bombed by German planes, the convoy of children separated into smaller groups and walked to Armavir, a settlement in Krasnodar Krai, where they were given horse carts with which to continue their journey. Forced to beg for food as they travelled, a small group of these children reached Beslenei and asked for shelter on August 13, 1942.

The chairman of the kolkhoz, Khusin Lakhov, called a meeting of the village elders who promptly decided the children were too frail to continue towards Teberda, their desired destination in the mountains further south. Two of the elders argued against harboring the children for fear of German reprisals against their families. Murzabek Okhtov argued that to reject the children would violate adige khabze, the Circassian moral code that values adopting orphans and extending hospitality to strangers. The council of elders voted to adopt all the children, 31 boys and one girl. The community understood full well that to harbor Jewish children was dangerous and so to mitigate the risk to the community and the children, they forged the household record book to make it appear as if the adopted children were born in Beslenei. All the children were assigned Circassian names.

The Germans marched into Beslenei soon after the children arrived. Murzabek Okhtov, posing as a collaborator, was appointed mayor. The Germans were suspicious; they’d heard rumors that Jewish children had asked for shelter, but they were only able to identify one boy. He had been adopted by a childless woman who, by all accounts tried to hide him but was betrayed by a local collaborator. The Germans killed the boy. His adopted mother was found dead a few days later on the grave of the child she had tried to save.

The story of Beslenei highlights the courageous and principled actions of an entire community. To be sure, such acts were extremely rare. All the more reason the Circassian villagers stand out for their humanity and courage, for their willingness to risk everything for vulnerable children. As a researcher and writer, Beslenei was one of the fascinating tales of the Caucuses during the Great War, and one that bolsters my fragile faith in an etiology of goodness.

Source: Youmans, William L., and Sufian, N. Zhemukhov “Rescue and Jewish-Muslim Relations in the North Caucasus.” In Beyond the Pale: The Holocaust in the North Caucasus, edited by Crispin Brooks and Kiril Feferman, University of Rochester Press/Boydell & Brewer Limited, 2020, pp. 270-318